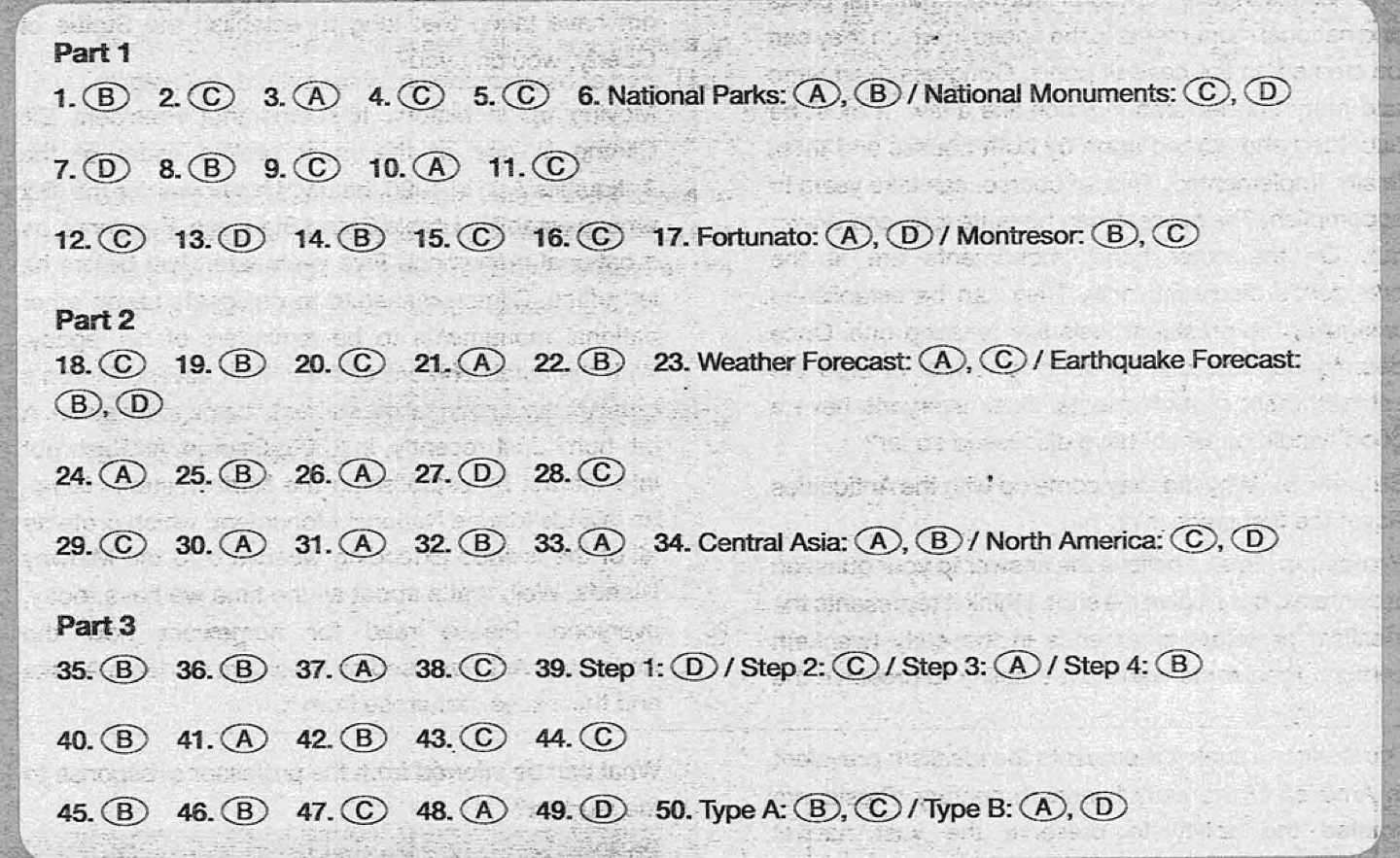

TOEFL IBT Listening Practice Test 18 from TOEFL iBT Actual Test Solution KEY

TOEFL IBT Listening Practice Test 18 from TOEFL iBT Actual Test Transcripts

Listen to part of a lecture in a history class.

Professor: Well, there is an act that presidents have relied on in the past to promote both the interests of the United States as well as their own. It is called the Antiquities Act. It was signed by Theodore Roosevelt in 1906, and it gives the president the power basically to block off public land owned by the U.S. government and declare it off limits to private enterprise and development. Let me try to state this a bit more clearly. The Antiquities Act gives the president the unobstructed power to designate land as national monuments, usually for conservation purposes. And, since its onset, eighteen presidents have used it.

Student A: But what about Congress?

Professor: Well, this has been the main issue with the act. Congress has little to no power in controlling what a president deems an antiquity and designates as a national monument. Now, let’s make this distinction clear, everyone. Congress does have within its power the ability to designate and name national parks. Parks, everyone, not monuments. The president, on the other hand, has the sole power to use the Antiquities Act to designate national monuments. We must make sure we separate the two. For example, Yellowstone National Park, the first in the United States as well as the entire world, for that matter, was established by Congress, in, let’s see here… yes, 1872.

Another distinguishing factor between national parks and national monuments is the speed in which they can be created. In the case of parks, Congress must write and ratify the declaration much like a law. It must be accepted and agreed upon by both houses and then, finally, implemented. This, of course, can take years to accomplish. The process can be quite long and drawn out. On the other hand, monuments are at the president’s discretion only. They can be established whenever the president feels like creating one. Once determined, little can be done to retract or stop the establishment of monuments. Does everyone have a good handle on what I have discussed so far?

Student B: Why did they come up with the Antiquities Act in the first place, sir?

Professor Well, I believe the answer to your question is complex, but I’ll give it a shot. I think it represents the idealism prevalent in America in the early twentieth century. Presidents wanted the ability to preserve the vast natural resources and land of the country. They wanted future generations to enjoy and benefit from what existed at the time in its unadulterated version. They also realized the potential of the areas’ exploitation in the future. In many ways, the future vision of the act and conservationsnal theme as well as of the presidents themselves is quite honorable. In essence, it was an attempt to preserve and protect the land for future generations. It was also established to remind future generations to appreciate and respect the world around them and to serve as a warning not to destroy ít. I mean… the vision of the early presidents as well as recent ones, everyone, in establishing national monuments is perhaps the one remaining good thing which links them together, this sense of responsibility of preservation.

Student A: Professor, which national monument was established first under the Antiquities Act?

Professor: Well, just a few months after the act was enacted, Roosevelt named Devil’s Tower in the state of Wyoming the first national monument. A couple of years after that, he established the protection of nearly one million acres of the Grand Canyon because, as he said, it was “an object of unusual scientific interest.” Another famous monument that resulted from the act is, of course, the statue of Liberty, which received its status thirty-eight years after it was presented to the States by France. You would have thought they would not have taken that long to establish the Statue of Liberty, wouldn’t you?

Moving up in history, it seems that President Bill Clinton is one of the most prolific users of the Antiquities Act. In 1996, he used his power for the first time to establish Utah’s Grand Staircase, Escalante, as a national monument. Five years later, just before he left office, Clinton managed to designate seven other national monuments to be reminders of his legacy. With the establishment of these final seven, Clinton’s grand total of national monuments came to nineteen. A lot, huh? Just recently, in 2006, George w. Bush got into the act by establishing the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument, which protects all of the islands extending westward to the Midway Islands. Well, that’s about all the time we have today, everyone. Please read for homework how the Antiquities Act was used by President Carter in Alaska and the issues that arose from it.

Listen to part of a conversation between a student and a professor.

Student: Oh, Professor Stevens. I’m glad I caught you. Are you on your way home because I wanted to talk with you a bit about my schedule next semester if I could?

Professor: Well, Angela, I was actually on my way home, but I can spare a few moments for you. Shoot!

Student: Oh, great, thanks, Professor. Well, I was planning on taking Dr. WhitJam’s humanities seminar. Do you think that is a good choice?

Professor: I believe that is an excellent choice. Even though he has only been here for a couple of years, I hear that his lectures are quite animated and lively. He still has that zest for instruction if you get my meaning. I do know that he can be quite demanding, too, which might tum off a lot of students.

Student: Yes. A friend of mine had him, and she said the same thing. I like challenging courses, so I think I would enjoy his. Great. Now, what about Professor Rice? Do you know her?

Professor: Of course I do, Angela. She’s the chair of the Religion Department. I believe she has a class on early Christianity next fall. Actually, she has been a good friend of mine for many years, and I consider her to be a topnotch lecturer and authority in western religions. Therefore, that’s another excellent pick in my opinion, Angela.

Student: Wonderful! I haven’t taken any classes in religion yet, but I’m really looking forward to hers. I just hope it isn’t full by the time I register. Usually, all the seniors and juniors fill the good classes up first.

Professor Well, if that happens, come talk to me, and perhaps I can put in a good word for you. How does that sound? I wouldn’t want you to miss out on her class.

Student: Wow, thanks for going out of your way for me, sir. That is very generous of you. Okay, um, I’m not keeping you too long, am I, because I need just a little bit more advice if you can?

Professor: No problem, Angela. Ask away.

Student: Well, the final class I wanted to ask you about is yours, sir. You’re teaching the folklore class, right? Yes, um, I was wondering if you were going to include any Zora Neale Hurston in the reading. She is one of my favorite African-American writers, and I was just hoping…

Professor: Oh, so you’ve been reading Zora, huh? Well, that is wonderful. Actually, no folklore class would be complete without exploring at least some of her work. I believe the early part of the class will focus on Hurston, and then we’ll branch out into other examples from the South. I’m in the process of reorganizing the syllabus, so I’m just not sure of the exact path we will take, but I can assure you that she will be one of the major writers we discuss.

Student: Oh, that’s great, sir! And I’m sorry for taking up so much of your time. I’ll let you know about the religion class, and I guess I’ll see you soon. Thanks again. Bye.